It seems counterintuitive that something associated with dampness and sweaty aromas could be used to help keep the body cool and dry. But a team of MIT researchers is looking at bacteria in a fresh way and using it in apparel that provides ventilation in response to body heat and sweat.

According to the researchers, the moisture-sensitive cells automatically sense and respond to humidity. Using genetic engineering tools now available, the cells can be prepared quickly in large quantities. The scientists are incorporating the live cells, which are safe to the touch, to construct moisture-responsive fabrics.

Working with a common, nonpathogenic strain of E. coli, the MIT research group tested the theory by engineering the cells to swell and shrink in response to changing humidity. The team was also able to engineer the cells to express a green fluorescent protein that causes the cells to glow under humid conditions.

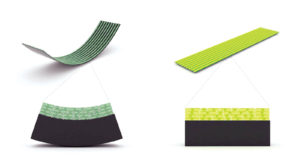

Using a cell-printing method they had previously developed, they printed the bacteria sheets on rough natural latex and tested the fabric’s response to changing moisture conditions. Under dry conditions, the fabric shrank; when wet, it expanded.

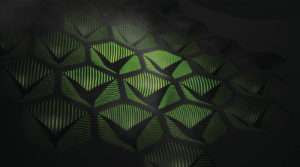

The researchers developed a breathable running suit that has a pattern of ventilating flaps featuring the cell-lined latex across the back. The size of the flaps and degree to which they open are tailored to accommodate the level of heat and sweat produced on different parts of the body. Like tiny sensors, they drive the flaps open when the wearer sweats and pull them closed when the body cools. In tests, the flaps effectively removed sweat from the body and lowered skin temperature. For more information, visit www.news.mit.edu.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG