For most people, arriving home from a hike covered in burrs would likely cause aggravation. But for George de Mestral, the burrs became an inspiration. Curious about how they clung so stubbornly to his clothes, the Swiss electrical engineer put them under a microscope, which revealed hundreds of “hooks” that attached to anything with a loop. Long story short, after years of experimentation and trial and error, he developed the hook-and-loop system known as Velcro®, patenting it in 1955. It represented not only a pretty handy way of fastening textiles and other materials together, it’s also one of the earliest examples of biomimetics, or nature-inspired innovation.

Manufacturers are increasingly turning to nature to guide innovation, says Chris Garvin, head of special projects for Terrapin Bright Green. Headquartered in New York City, Terrapin is an environmental consulting and strategic planning firm that assists with large-scale planning and design projects worldwide. Its “bioinspiration” efforts focus on increasing energy efficiency, developing sustainable production processes and creating ecologically driven metrics for factories, among other projects.

Bioinspired innovation falls into two distinct approaches, says Garvin. “One of them, bioutilization, is the use of organisms or biological materials to fulfill a human need,” he says. “The other, biomimicry, is the abstraction and translation of biological principles into human-made technology. It’s also a method of assessing whether a design concept is likely to ‘create conditions conducive to life.’ As companies look to be leaders within their industries, gain market share and tackle the challenge of climate change, the opportunities presented by bioinspiration are unmistakable.”

Consequently, says Marie O’Mahony of O’Mahony Consultancy, a wide range of biomimetic products are turning up in all kinds of variations. O’Mahony, whose company is based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, is a professor, author and curator specializing in advanced and smart textiles. Along with Velcro, she mentions sharkskin (the inspiration for Speedo’s® Fastskin swimsuits) and the lotus leaf (the inspiration for Schoeller’s NanoSphere®) as other biomimetic examples.

There are two reasons companies should be interested in producing or utilizing nature-inspired technology, says O’Mahony.

“The first is the environmental benefit,” she says. “The second is the growth of the consumer market for these products. One of the things nature does extremely well is using the least amount of material and energy—something we humans often struggle to do. Today, consumers want to have smart, advanced materials that do wonderful things for the body, their home and place of work, but without compromising the environment.”

And because biomimetics commonly combine different capabilities—such as hard/soft or rough/smooth—within a single structure, O’Mahony believes textiles will increasingly provide the solution.

Creating responsive fibers

it from cooling. Celliant technology recycles and converts radiant body heat into infrared energy, sending this back to the tissues.

Photo: Courtesy of Salewa Jacket and

provided by Celliant/Hologenix LLC.

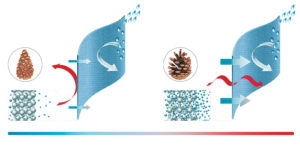

Jeff Dugan is vice president, research, for Fiber Innovation Technology (FIT) Inc. Headquartered in Johnson City, Tenn., FIT is part of the Cha Technologies Group, a global group of companies focused on specialty fibers and fabric products. FIT produces specialty spun-melt stable bicomponent fibers and those using unconventional polymers for a clientele that includes nonwovens producers and other customers within a wide variety of industries. Among FIT’s offerings is a fiber that mimics the “pinecone effect,” making it responsive to changes in environmental humidity.

As Dugan explains, pinecones bind their scales/leaves very tightly when they first drop, keeping their seeds inside of them. When conditions are warm and dry—ideal for seed germination—the scales turn outward, releasing the seeds. Cold, wet conditions cause the cone to remain tightly bound.

“We had done some work on fibers that curl in response to heat and so we were approached by MMT Textiles Ltd., which wanted a fiber that would curl in response to moisture and then reversibly uncurl when dry, and then repeat that cycle endlessly,” Dugan recalls.

The result was Inotek™, an off-center sheath/core fiber with a polypropylene core and a nylon sheath. The core absorbs no moisture; the sheath absorbs about 4 percent moisture, swelling as it does so and causing the fiber to curl into a helical shape. A fabric made from yarns spun from these fibers will become tighter when wet.

“This opens up the interstices between the fibers to a greater degree, so the fabric becomes more breathable when wet and less so when dry, since the fiber straightens out when dry. This allows uncomfortable moisture vapor to escape when a garment-wearer is sweating but provides insulation when dry, to prevent over-chilling after physical exertion is finished,” Dugan explains. (The Inotek fiber is sold by MMT Textiles and is undergoing evaluation by several “well-known garment companies.”)

Dugan says biomimetics shows good potential, evidenced by the fact that existing solutions have resulted in growth. “And there are still problems to be solved and relatively few that are currently being addressed with biometric solutions,” he adds, mentioning FIT has another biometric development in the works.

Converting body heat

How plants convert sunlight into energy and the way bodies make vitamin D from sunlight provided the idea behind Celliant® technology, says Seth Casden, CEO of Santa Monica, Calif.-based Hologenix LLC.

Casden founded the company in 2002 with David Horinek, cofounder and inventor of technology. In researching treatment options for his grandmother who had various physical issues, Horinek became interested in infrared light.

Infrared light acts like a vasodilator, stimulating the mitochondria in the cells, promoting circulation, improving cell oxygenation and producing energy. It’s commonly used as a therapeutic treatment for maladies such as high blood pressure, congestive heart failure, rheumatoid arthritis, muscle tears and other ailments, says Casden.

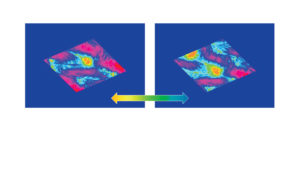

No single organ in the body generates energy for every cell, he explains. Instead, energy is made within each cell individually, and requires oxygen to do so. Unaided, getting oxygen from the blood to the cells is extremely difficult. Celliant is able to address the “significant inefficiencies” in the process by recycling and converting radiant body heat into infrared energy, sending it back into the tissues and muscles, resulting in increased oxygen delivery.

“There are certain minerals that absorb heat and give off infrared light,” Casden says. “We’ve miniaturized these minerals [Celliant technology utilizes ceramic-based minerals such as titanium dioxide, silica and aluminum oxide, among others], putting these into polyester when that material is in its liquid stage. Once extruded into fiber, the Celliant mineral additive is in it and becomes part of the material, lasting its lifetime.”

In June 2017, the company received approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) allowing it to claim that Celliant increases blood flow. (Clinical tests demonstrated an increase in tissue oxygenation equal to or greater than what is achieved by medicine designed to increase blood flow.)

Celliant minerals can also be added to nylon and then blended with any other type of material, such as wool, cotton, Lycra® or Tencel®, says Casden. The technology is licensed to manufacturers—a garment company, for example—who would purchase the raw material from Celliant’s approved supply chain. The material is used for a spectrum of textile applications, including apparel and bedding, as well as in the health care and veterinary markets. In some cases, Celliant will manage the supply chain and also make some products, like socks and sheets. End users include brands like Harley-Davidson®, Hammacher Schlemmer, L.L. Bean®, Bear Mattress and others. The company expects to make a major announcement during the first quarter of 2018 regarding a leading sports brand.

Plant-inspired protection

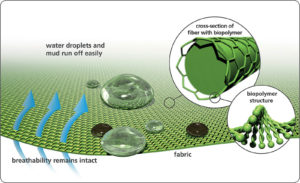

Schoeller Textil AG is headquartered in Sevelen, Switzerland; Schoeller Textil USA Inc. is located in Newburyport, Mass. As previously mentioned, the company produces NanoSphere, a self-cleaning, dirt- and water-resistant and abrasion-resistant textile finishing technology inspired by how the leaves

of certain plants remain clean.

A relatively new finish is ecorepel® Bio, which also imitates that same natural protection, says Stephen Kerns, president of Schoeller USA. According to Kerns, the high-performance, permanently odorless finish offers a “level of durability not seen before with other Bio products.”

The finish is PFC-free and made entirely from renewable, primary products—agricultural products not used for foodstuffs or animal feed. It completely envelops the fabric’s fibers, providing a repellent effect that allows water droplets, certain oils and aqueous dirt to run off the surface. Ecorepel Bio, bluesign® approved, can be applied to a variety of textiles (cotton, polyester, nylon and others) ranging from active-mountain and technical streetwear to fashion weaves, says Kerns. Schoeller also introduced another PFC-free, bluesign-approved finishing technology, 3XDRY® Bio.

“Both were the result of further development and response to the continued demand for sustainability,” says Kerns. “Sustainability is deeply embedded into Schoeller’s corporate mission and is constantly further developed.”

Schoeller has also worked with spider silk and has other nature-based fibers under redevelopment. And its c_change® technology—a waterproof/windproof membrane inspired by a pinecone’s reaction to temperature change—continues to experience strong demand, primarily from those offering outdoor and lifestyle performance outerwear, since the technology ensures optimum body climate.

“Mother Nature has been a great inspiration for our technical solutions for many years,” says Kerns. “Our leadership continues to focus on biomimicry, and more of our brand partners—including larger brands like Patagonia®—are seeking it out.”

Managing body moisture

“Just as animals and plants use the moisture from the air to balance their needs, they also use their internal moisture as part of their bodies’ balance,” says David A. Gray, founder of MedTextra™ LLC. “This is what MedTextra does. It’s a system providing a measured, balanced approach to moisture within the cross-section of the materials we put next to our skin.”

Headquartered in St. Paul, Minn., MedTextra is a subsidiary of the Liberman Distributing and Manufacturing Company (trade name Lidco Products; Gray is CEO) also in St. Paul. Motivated by his wife’s serious illness, he noticed that few chemotherapy patients wore face masks to protect themselves from viruses, in part because these were uncomfortable to wear. Gray turned to nature for a solution for this and other issues, ultimately settling on one utilizing the body’s “breath,” whether through actual exhalation or evaporation.

“We created a proprietary fabric system which advances active ingredient delivery using the body’s own moisturizing,” Gray says. “We also created it so that it performs multiple functions for active material placement and filtering activity as well.”

The MedTextra yarns can be embedded or pre-coated with various active agents, ranging from antiviral to dermal, allowing the yarns to deliver the benefits. The yarns can also capture ingredients actually placed on the body—creams, lotions, oils and ointments—with the polymeric fibers constantly moving and refreshing these ingredients, using the body’s moisture to keep them active for longer periods of time.

“The choice of these actives is up to the product manufacturer and their intended customer,” Gray explains. “We can also vary the level of our polymeric materials to balance the moisture level for various applications. Other fibers, such as polyesters, cottons, etc., can be used in conjunction with ours; all the benefits of the other fibers remain in force.”

Face masks can be treated with an antiviral agent kept active by the breath’s moisture and constantly refreshed by the fibers’ ionic motion. Such activity would “bring in new capturing and killing agents to the mask’s cross-section of material,” says Gray, mentioning that some of the company’s tests demonstrated that moisture remained on masks with MedTextra’s yarn for over five days in “desert-dry conditions” as opposed to standard masks that dry out in a couple of hours. Other opportunities for the yarn include apparel, textiles, even airlines (“Imagine an airplane air filter pre-treated to kill viruses,” he says). MedTextra is currently looking for partnership or licensing opportunities to bring the technology to market.

Awareness and challenges

Terrapin’s Chris Garvin says awareness of biomimetics and bioinspired innovations is growing, especially among the scientific community. And the industrial design and agricultural design communities are paying attention as well.

“But a major challenge for these communities is the innovation gap between the basic science and direct application of these scientific discoveries,” he says. “The effort to translate a scientific discovery into a viable product can take years and millions of dollars.”

Another challenge is positioning these innovations, says O’Mahony. “Many have potential applications ranging from medical to sportswear and intimate apparel,” she says. “Interestingly, I do see specifiers being very open to the cross-sector mobility of biomimicry-inspired textiles, which is great for the development of this industry.”

For the textile industry, biomimetics holds the potential of creating products with unique properties that use fewer raw materials and less energy in production, creating higher-value materials in the process, says Garvin.

“The risks of innovation are high; many failures occur before the breakthrough that changes an industry or even the entire world,” he says. “[But biomimetics] offers a design process for finding unique approaches to solving today’s most vexing challenges.”

Pamela Mills-Senn is a freelance writer based in Long Beach, Calif..

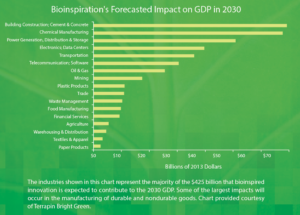

“Bioinspired innovation has the potential to transform large segments of the U.S. economy by increasing both gross domestic product [GDP] and employment,” asserts Chris Garvin, head of special projects for Terrapin Bright Green, a New York City-based environmental consulting and strategic planning firm. Garvin cites Fermanian Business & Economic Institute figures estimating that by 2030, bioinspired innovation could account for approximately $425 billion (valued in 2013 dollars) of the U.S. GDP and could generate about two million jobs by that same time.

“Beyond 2030, the impact of bioinspired innovation is expected to grow as knowledge and awareness of the field expands,” he adds. “The largest single-industry contributions are expected in building construction—including the cement and concrete sector—chemical manufacturing, and the power, generation, distribution and storage sectors. But some of the largest impacts will occur in the manufacturing of durable and nondurable goods, due to the increased use of new bioinspired materials and processes.”

“Beyond 2030, the impact of bioinspired innovation is expected to grow as knowledge and awareness of the field expands,” he adds. “The largest single-industry contributions are expected in building construction—including the cement and concrete sector—chemical manufacturing, and the power, generation, distribution and storage sectors. But some of the largest impacts will occur in the manufacturing of durable and nondurable goods, due to the increased use of new bioinspired materials and processes.”

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG