Although the automotive industry is subject to ups and downs, one fact remains steady: It’s an attractive market for specialty fabrics

by Pamela Mills-Senn

In an ever-changing world, there are few constants. But one constant is this—people love their cars. They may grumble about traffic. They may rend their garments over breakdowns and costly repairs. They may sob profusely over high insurance rates. But one thing they’re loath to do is give up driving and the freedom that comes with it. This is one reason why suppliers of textiles to the automotive industry feel this love affair will dampen the demand for totally autonomous technology.

D. Paul DiMaggio Jr., CEO of Delaware Valley Corp., is one such supplier. Located in Lawrence, Mass. (with plants in Tewksbury and Lawrence), the company manufactures nonwoven fabrics from synthetic fibers into flat felts, velour/dilour fabrics and patterned/structured fabrics.

“From my perspective, auto manufacturers will not see the self-driving car as a large market for decades to come, if ever,” says DiMaggio. “I believe they may be overreacting to the belief that we, the consumer, will ever let go of the control of our driving experience.”

Even if vehicles equipped with this technology were to become ubiquitous, the impact on suppliers is hard to discern, although the potential for declining vehicle ownership is there. However, self-driving taxis in metropolitan areas and services like Uber or Lyft could prove a different story, says DiMaggio, who thinks as they proliferate, auto sales will slump. Consequently, he says, “change is in the wind for automobile manufacturers and all their suppliers.”

The company primarily produces fabrics for other manufacturers as part of their finished products or for their manufacturing processes, as well as for wholesale entities that rebrand and market its fabrics. In addition to OEM and aftermarket automotive, Delaware Valley also serves the medical, industrial, construction, roofing and marine markets. In automotive, its flat- and velour-finished interior fabrics are used as the finished surfaces on package trays, door panels, trunks and cargo areas. Its nonwoven seating fabrics are used for bolsters, close-outs and seat backs. The company also produces automotive under-panel and wheel well liner constructions, which DiMaggio describes as “a relatively new product to OEM needs.”

Nonwovens have traditionally served multiple purposes, for instance reducing squeaking where a seating fabric might rub against a metal or plastic panel, with the pile surface of the fabric completely eliminating squeaking in many cases. Nonwoven pile fabric also improves interior acoustics by reducing internal echoes, road noise and “attenuating internal sound waves,” he explains.

But recently, the demand for nonwovens has started to weaken. These fabrics are being removed from door panels and rear cargo areas, replaced by hard plastic, possibly to impart a more modern look. But this is to the detriment of internal acoustics, says DiMaggio. Additionally, nonwovens have vastly improved.

“New patterned nonwoven fabrics as well as multicolored additions of yarns to velour fabrics, in our opinion, have been missed by designers and should be looked at more closely,” DiMaggio says. “With the new lower-pile, cleaner-looking nonwoven fabrics, perhaps designers will look at these anew, thereby keeping the clean looks and improving internal acoustics.”

There have also been “huge leaps” in terms of the sustainability of nonwovens, particularly when it comes to recyclable constructions. The entrance of thermal-bonded nonwoven velour fabrics “changed the landscape,” paving the way for these fabrics to be 100 percent recyclable, he says.

“[We] were a major leader in this change,” says DiMaggio. “Prior to the thermal-bonding process, nonwoven carpets were bonded with water-based resins that precluded them from any sort of recycling. Now, the new fabrics are bonded in a manner making them totally recyclable, even into re-extrudable pellets.

“There is no question about it,” he continues. “Sustainability and recyclability have been a major focus in automotive design, and fabrics are very much involved in this improvement.”

The automotive industry is cyclical, DiMaggio says, and now there are indications it’s heading into a downturn cycle, potentially affecting capacities, pricing and margins for perhaps the next several years.

“Fabric producers will have to increase their work relationships with auto manufacturers,” he cautions. “And auto manufacturers will have to become more open to ideas presented to them for all to succeed.”

Smart opportunities

A concern over sustainability is also being seen by Apex Mills’ buyers, says Jonathan Kurz, owner and CEO of the company. Headquartered in Inwood, N.Y., Apex creates warp knit textiles, working in collaboration with several Fortune 100 companies to develop technical solid knit textiles, mesh netting and 3D spacer fabrics (“Ideal for noise reduction,” says Kurz). The company partners with suppliers like the Bloomfield Hills, Mich., Acme Mills Co. that aggregate and manufacture resources for the automotive industry. Its fabrics are used in products like wind deflectors, cargo nets, seating and shade cloth.

But smart textiles are also receiving a lot of attention. In fact, says Kurz, this is where the trends are going. The company is conducting research in this area, for example working with Drexel University in Philadelphia to develop touch sensors integrated into fabric. These could allow someone to, for example, turn something on or off by merely touching the fabric. Apex Mills is also a member of the Advanced Functional Fabrics of America (AFFOA), a nonprofit institute headquartered in Cambridge, Mass.

Although still a work in progress for this industry, vehicles represent an excellent opportunity for smart fabrics and textiles, says Kurz.

“Soon, smart textiles will be able to provide light, change colors, incorporate sensors, change temperature and more,” he predicts. “We see this as an [area] where our dedicated research and development can play a major role.”

Kurz says that rather than being out in the open, most of Apex Mills’ industrial fabrics are deployed as support for certain features.

“For instance, automotive seats and seat backs contain foam cushioning for comfort and breathability,” he explains. “Strong mesh fabrics are also used to reinforce and insulate the foam. Our fabrics are also used as laminating substrates for certain upholstery materials.”

As for fabric qualities deemed most important, in addition to flame resistance, lightweight fabrics are desired, propelled by the popularity of electric and hybrid vehicles, “The lighter the fabric, the better the vehicle’s performance,” he says.

People are also looking for options offering a degree of customization when it comes to color, comfort level, noise reduction, specialty trim and so on, requiring the company to stay well in front of emerging trends, Kurz explains.

“We’ve expanded our dyeing and finishing capabilities and can create colors across the spectrum we can customize for a manufacturer,” he says. “Manufacturers are also looking to reduce costs and in response, Apex Mills is working with advanced fiber manufacturers that offer fire resistance at a lower price.”

And because the pricing of eco-friendly textiles is higher, the company is also exploring various options, working with fiber manufacturers to lower the costs of recycled and sustainable textiles.

Aftermarket activity

Ask Dee M. Duncan Jr., CEO of Keyston Bros. Inc., how the recession affected his company and he’ll tell you business was great, at least for the company’s automotive market. The Roswell, Ga., wholesale fabric distributor provides interior aftermarket product for vehicles, with trim shops comprising its primary customers. (For those unfamiliar, trim shops will do things like repair ripped seats, replace flooring or headliners, or customize vehicle interiors.) Other markets the company serves are marine, outdoor, contract and furniture.

“In 2007 and 2008 people stopped buying cars,” he explains. “They were keeping them a lot longer and fixing them up, so that was very good for us. But the last three years have gotten a little weaker, because now people are buying cars. However, over the last 12 months this has slowed down a bit so we’re seeing an uptick.”

Keyston Bros. is also noticing more customization, with people upgrading or enhancing their interiors. What Duncan is not seeing is the use of cloth fabrics for seats and panels. There’s less and less of this, with leather the material of choice. Vinyl, especially vinyl that looks like leather, is also popular, particularly among the more value-conscious shoppers.

Although the need to replace flooring has declined—thanks to people taking better care to protect their carpets—headliner replacements are common, with hot, humid climates causing these to give way. The patterns have changed to flat-knit polyester solution-dyed materials, which impart a woven, rather than fuzzy (outdated), appearance.

“The biggest thing I’m trying to achieve in this marketplace is taking time out of the trim shop process by offering quilted vinyl and quilted leather,” says Duncan, adding that Keyston Bros. also does its own perforating. “We’re introducing this now on the West Coast and we’re going

to roll it out from there.”

Nonwoven advancements

With quieter vehicle interiors increasingly considered an indication of quality, suppliers and manufacturers in the automotive market are pressured to deliver products that help reduce cabin noise, yet still meet the industry demand for lower-weight vehicles and cost reductions that don’t compromise noise-reduction capabilities, says Keith Hayward, managing director of Monadnock Non-Wovens LLC. Located in Mount Pocono, Pa., the company produces polypropylene nonwoven meltblown and acoustically tuned meltblown composites for the filtration and insulation markets.

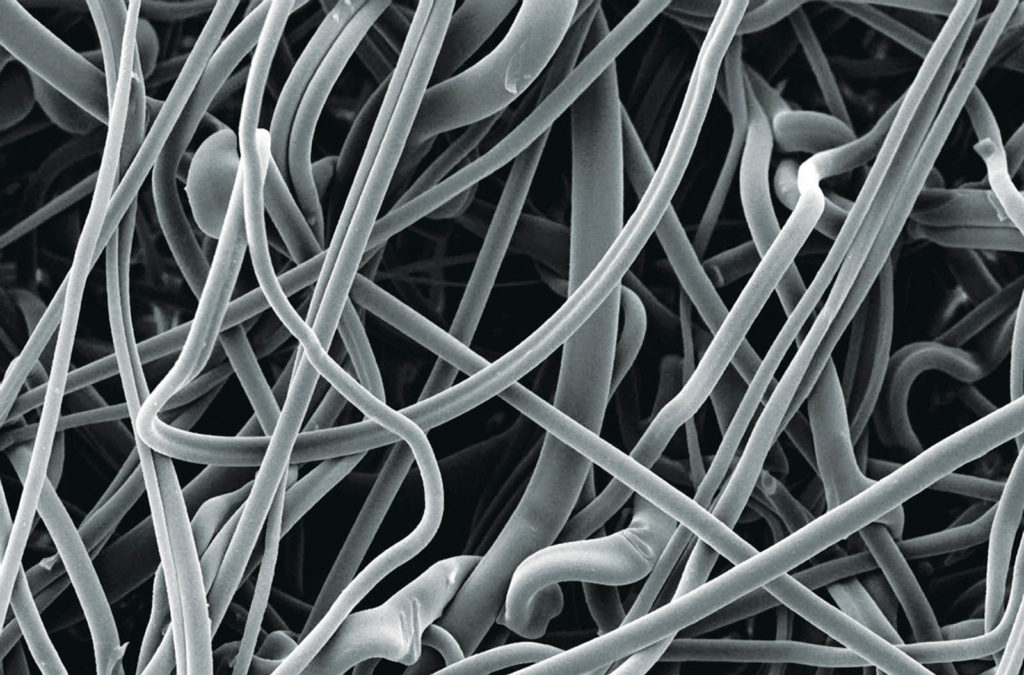

The materials are used in various places throughout the vehicle, such as in the headliner, pillars, trim panels, trunk systems (sidewalls, deck lids and spare tire covers), in the cargo area (sidewalls and load floors), and in the doors and instrument panels, says Hayward. The company has been manufacturing acoustic insulation for cars for more than 15 years, with its latest offering—HPAM™, or “High Performance Acoustic Media”—a low-cost, low-weight fine-fiber polypropylene lofted media, providing “significant improvements in low-frequency absorption.”

Automotive manufacturers are also pressuring suppliers to reduce the environmental impact of older technologies like polyester blends and foams, says Hayward.

“Sustainable materials and sustainable manufacturing processes are important to consumers,” he explains. “A good extra benefit of HPAM is that it is fully recyclable since it’s made from pure polypropylene rather than blends of polymers in older designs. Monadnock also manufactures all of its products with renewable electricity, and all waste by product from the manufacturing process is recyclable.”

Where is the automotive industry heading? What will it value? Think sustainability, light weight, space reduction for fuel efficiency, recyclable, low cost and safe, says Hayward, adding that fabrics and textiles with engineered performance will play a “prominent role” in achieving these objectives.

Pamela Mills-Senn is a freelance writer based in Long Beach, Calif.

Located in Solon, Ohio, The Quality Thread & Notions Co. at one time provided threads, zippers, hook and loop, and other products to the apparel industry. It shifted away from that arena in the mid-1980s as apparel production drifted overseas. Now, Quality Thread targets the industrial sewing markets, among them, awnings, canvas and tents; umbrellas and outdoor shade structures; pool and spa covers; tarps and covers; outdoor furniture; boat covers, enclosures and upholstery; and automotive interiors. One of the company’s customers is The Miami Corp., a Cincinnati supplier of upholstery fabric, outdoor fabric and upholstery supplies. Miami Corp. distributes fabrics to a variety of markets including automotive, providing vinyl, cloth, leather and carpets, as well as interior and exterior trim products like foam, convertible tops, car seat heaters and fasteners. “Durable and reliable threads are key to any manufacturing process,” says Michael Pessler, coach and seat specialist for Miami Corp. “Compatibility to in-house sewing machines is equally important. We’ve found that polyester thread is becoming more prevalent in the automotive industry due to the vibrant colors offered and overall perceived higher durability.” He mentions in particular Sunguard threads, one of Quality Thread’s best sellers. The custom-color line matches 36 of the most popular acrylic fabrics. The colorfast threads are manufactured to meet anti-wick standards, reducing seam leakage. Pessler says threads no longer strive for invisibility, at least not in every case. Instead, the trend appears to be lighter-weight polyurethane vinyls with contrasting thread colors, such as a black interior with a bright red thread. “Most threads used are the 92 weight, but there does seem to be a slight demand growing for 138-weighted goods,” he says. “The vast majority of manufacturers seem to care about durability, longevity, etc. However, some builders insist on the lowest-cost option to complete a build as their customers often upgrade, trade or sell their vehicles within a three-to-five-year period. [But] thread issues are rarely seen in the auto industry on our end—soft goods seem to deteriorate much quicker than threads ever do.”

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG