As climate change and pollution concerns remain at the forefront of public attention, textile companies work to give themselves an eco-friendly edge.

by Jeff Moravec

A decade ago in this magazine, the growing attention to sustainability in the textile supply chain was a hot topic. Guess what? It still is.

This doesn’t mean the industry hasn’t made progress. But the depth of the issue precludes an overnight fix. Companies continue to work to improve sustainability in their operations and output, often in new and innovative ways—and with deeper dedication. From a cross-section of organizations on the front line, we found out how important this topic is in the specialty fabrics industry, and where change is happening.

A global circular economy

“Sustainability is woven into all initiatives at DuPont™ Biomaterials,” says Renee Henze, global marketing director for the company, which, from its location in Wilmington, Del., develops high-performance, renewably resourced materials. “And we’re always working towards launching new sustainability-focused initiatives.”

Recently, Henze says, the company has highlighted the application of its DuPont Sorona® as a “versatile, long-lasting and fully recyclable replacement to spandex, or elastane. We see Sorona as a more eco-friendly alternative for brands and manufacturers as high-performance apparel will stay in consumers’ closets longer and out of landfills.”

According to Henze, Sorona is a 37 percent plant-based fiber, helping to minimize its environmental impact, while offering fabric spinners and mills, textile manufacturers and apparel brands key performance attributes. The fiber is used in a variety of apparel applications, including ready-to-wear, luxury fashion, sportwear, swimwear and intimates.

But there are plans for additional applications as well, she says. “Sorona fiber will be leveraged for collaborations in faux fur, footwear, higher-stretch applications and increased renewable content,” according to Henze. “In the long-term, our goal is to be an integral player in the global circular economy, so as an industry we can develop renewable, sustainable products that support a process that is responsible and restorable.

“DuPont has spent over a century creating textile products that transform the way people live and work, and bio-based materials have helped us do so more sustainably,” she adds. “We’re committed to finding ways to enhance quality of life through high-performance products, while progressively reducing the environmental impacts of industry.”

In addition to Sorona’s sustainable sourcing and composition, Henze says DuPont Biomaterials has deepened its commitment to sustainability through collaborations with industry peers, involvement with third-party, reputable industry organizations, and a dedication to creating products that are awarded industry certifications.

Most recently, DuPont Biomaterials was a part of several collaborations and collections, including a collection of insulation products that leveraged Sorona fiber and Unifi’s REPREVE® recycled PET, offering benefits that reduce environmental footprint without compromising on insulation performance. The company also collaborated with NIPI™, the maker of Thindown®, to create a down fabric with the combined properties of down and Sorona to yield a material with design flexibility, sustainability and increased warmth retention.

Intelligent innovations

Sustainability has been a priority at Duvaltex since CEO Alain Duval’s grandfather founded the textile producer (then called Victor, its first brand) nearly three-quarters of a century ago in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. “Early on,” he says, “we were recycling wool, yarn and leftover fabric, transforming them into new products such as blankets and overcoats.

“How long have we been interested in sustainability? A long time,” says Duval.

The company has been known as Duvaltex since 2015, and with four brands (Victor, True, Teknit, and Guilford of Maine®), Duval says it is North America’s largest contract textile manufacturer—and is more committed to sustainability than ever before.

In 1999, about 10 years after Duval became chief executive officer, the company chose to work with the environmental consultancy McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry to establish a more formal path to sustainability. The first step was to analyze and assess Victor’s products and processes based on the following criteria: product/material transparency, material and chemical input safety, recyclability and recycled content; renewable energy and resource efficiency; increasingly sustainable manufacturing processes; water quality and conservation; and social responsibility.

As it turned out, that was part of the beginnings of the Cradle to Cradle® (C2C) concept developed by William McDonough and Michael Braungart to limit a product’s environmental impact, a concept that became popularized following their 2002 book.

As a result of its work with the consultant, in 2001, Victor introduced the concept of Eco Intelligence Initiatives, aimed at reducing the impact of textile manufacturing on the environment and human health. Two years later, the company launched its Eco Intelligent® polyester, the first antimony-free polyester for commercial interiors made with safe optimized dyes designed to be perpetually recycled in a closed-loop system of manufacture. It was also chlorine-free, free of persistent bioaccumulative toxic (PBT) chemicals, produced with renewable energy and made with sustainable manufacturing practices.

The company’s continued focus on sustainability includes the introduction this fall of the first recycled biodegradable polyester textile for commercial interiors, Clean Impact Textiles™. “It’s a major step forward in establishing an advanced bi-circular economy model for textiles whereby polyester fabric, at the end of its useful life, can flow through either a biological or technical cycle,” says Duval.

This technology, he says, allows Duvaltex to create high-performance fabrics that are long-wearing in commercial interiors, but that can biodegrade in landfills and wastewater conditions at a rate similar to that of natural fibers. It’s done through the addition of a bio-catalyst in the yarn extrusion process that enables anaerobic digestion in landfill and wastewater treatment conditions.

“This has not been done, as far as we know, but certainly not in our industry,” says Duval. “It’s important, we believe, because even if you have a closed-loop circular economy, a product that could be recycled would still at some point go back to the earth and it would have an impact. So having product that after a little over three years is biodegradable is a big innovation compared to a polyester that could go in the landfill and take 100 or 200 years to degrade.”

Duval wouldn’t reveal what advancements are on the horizon for the company. “But investing in research and development is a priority for us,” he explains. “The future is based on innovation, and working with a lot of strong partners, trying to solve the problems of the planet. We’re always looking for the next big innovation.”

Green partnerships

Hohenstein, headquartered in Germany, is not a textile producer but an industry partner that helps companies with their product development and sustainability efforts, including meeting certification standards of the OEKO-TEX® association (of which it is a founding member).

So does a textile manufacturer just wake up one morning and decide to be more sustainable?

“Typically, it’s a longer journey than that,” says Ben Mead, manager director for Hohenstein Institute America, who works out of an office in Ligonier, Ind. “It might be a change in ownership or leadership, a more strategic approach.”

Very often, according to Mead, a company already has a product or a long history, “but they recognize that customers are becoming more and more focused on knowing what has gone into the product—how it’s made, where it’s made, and who is making it.”

“Those companies realize they have an opportunity, or recognize this is a trend,” he adds. “Even though they may be already considering their sustainability impact, they want to be more intentional about that. They know they need to do more if they are going to continue to be successful.”

Hohenstein also works with fledgling companies that want to focus on sustainability from the minute they open their doors. “They are born and bred from a younger generation that has decided, from the very beginning, to consider not just cost of performance and durability but also the sustainability aspect,” says Mead. “They see a need and are going to build a product, but want to make the right choice with the supply chain or material choices.”

STANDARD 100 by OEKO-TEX certified textiles are tested for harmful substances and are safe for human ecology. Some companies can be surprised by the rigorous nature of the certification process, says Mead.

“They see competitors in the market and they assume their product is better, so they should be able to go through certification pretty quickly,” he explains. “In some cases, they find out a little bit about their product and they realize this certification is truly rigorous. It’s a robust process, not simply a matter of applying and paying the money. The product has to qualify.”

Given increasing consumer attention to sustainability efforts, Mead says Hohenstein has seen a significant uptick in its business in the past 18 months or so. “That’s companies wanting to certify products, but we’re also hearing from consumers,” he says. “If they see certification on a product, or marketing from a retailer with which they are familiar, they want to know what it means. There’s a level of understanding about all this that is really increasing.”

Sustainable solutions

Huntsman Textile Effects, a division of Huntsman Corp., is a global provider of high-quality dyes, chemicals and digital inks for the textile and related industries. The company brings innovations in textile dyes to brands and retailers around the world, offering sustainable solutions that drive performance and meet ecological requirements.

“With the tightening of regulations and enforcement of stricter standards to meet consumers’ demand for a cleaner and more transparent supply chain, sustainability will become an increasingly prominent way to demonstrate competitive differentiation going forward,” says Brook Swinston, commercial director for the company’s American operations, based in Charlotte, N.C.

Swinston refers to the company’s AVITERA® SE reactive dyes as an example of its commitment to sustainability. AVITERA SE delivers water, energy and CO2 savings of up to 50 percent compared to conventional dyeing technologies and are free of para-chloro-aniline (PCA) and other hazardous substances, he says, while also helping mills improve productivity and yield, providing businesses with a cleaner supply chain.

One task in transitioning to more sustainable products is to help mills look at the big picture and plan for their long-term success, according to Swinston—including understanding the value of a product, which may seem more expensive than less eco-friendly alternatives.

“We work with mills in terms of life cycle costs, rather than unit costs, and we aim to try to get them to think that way through value drivers,” says Swinston. “The best mills are turning around and listening, ensuring that they buy the most sustainable dyes and quality textile chemicals. But sustainability is not yet mainstream thinking in a lot of mills. Getting contract mills to collaborate and join us on the journey in building a sustainable future is key to driving the change in the textile industry.”

Swinston says his team works not just to sell products to mills, but to partner with them so they better understand the value of working more efficiently and reducing environmental impact. “We don’t want to be just a firm that makes products; we’d like to be known as a trusted advisor,” he explains. “Issues are often brought to light from a competitive peer who has not been able to provide an ecological solution, and they come to us for help.”

Because consumers are price sensitive as well, and products that improve sustainability may cost more, says Swinston, there is a need to raise awareness among brands and retail institutions for the industry to make the necessary transition to more environmentally sustainable and economically viable business models. “We need to continue to reinforce the importance of sustainability. That’s something the industry is grappling with right now and we are going to steadily get there,” he says.

Embracing biomimetics

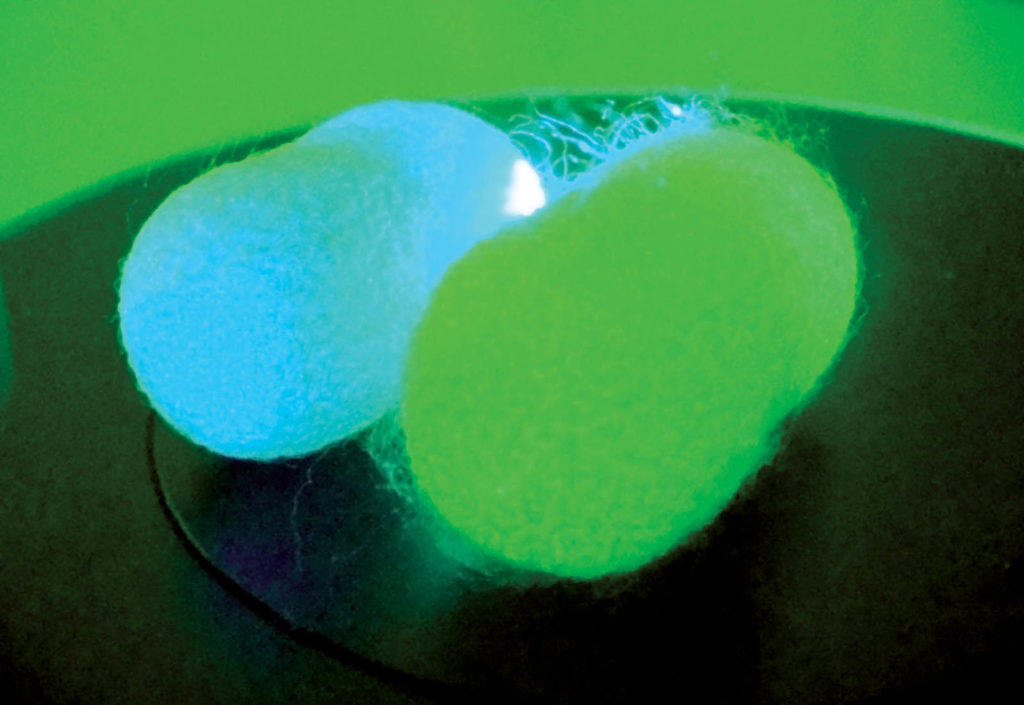

No one knows for sure when the discovery was made that silkworm cocoons could be used to produce a luxurious fiber. The process was a closely guarded secret, “the Coca-Cola of its day,” at least four millennia ago in China, says Jon Rice, chief operations officer for Kraig Biocraft Laboratories Inc., based in Ann Arbor, Mich. And while silkworms still chomp on the leaves of the white mulberry tree to produce those cocoons, Kraig uses technology—splicing in spider genes—to make a recombinant silk with strength and flexibility far exceeding mundane silk.

Kraig has changed the “recipe” for silk by using genetic modification, according to Rice, but continues to rely on traditional, “very ancient processes” to extract the fiber.

That stands in contrast with competing techniques (or synthetic alternatives) for spider silk, he says, that use chemicals and generate greenhouse gases—and are more expensive.

“We let nature do the work for us,” he says, which reduces the environmental impact of producing the silk.

The key, says Rice, is changing the silkworm’s DNA, “which took years of work in the laboratory.

“Our silkworms are happy to go about their life, and when it comes time to make silk, they go pull up the recipe page for silk,” says Rice. “But now, instead of making the silk a traditional silkworm would make, they start producing this higher-strength, high-elasticity version of silk protein.”

“We create a parent strain in the lab, and then the next generations continue to carry those fiber performance properties forward,” he explains. “Then it’s simply a matter of scaling up the number of silkworms, generation after generation, to produce a commercial production platform for recombinant spider silk.”

Not all strains are the same because the applications require different characteristics. “We look at ways to impact strength, elasticity or a combination,” Rice explains. “There are applications where high strength is good but elasticity isn’t.” For example, protective materials produced for the military, he says, may need superior strength but low elasticity so they can absorb an impact without moving.

“It’s amazing what we can do with new genetic engineering tools, but I think we’re just scratching the surface of what’s possible,” says Rice. “Our wish list of ideas and things we’re looking to pursue for spider silk far exceeds our funding at this point. But as we grow, we’ll be able to explore more interesting approaches.”

In some ways, he adds, the textile market is “low-hanging fruit. We’re starting to look at things like medical applications. Since spider silk is biocompatible, it can be great for a medical suture or other imbedded material. It doesn’t have an interaction with the body. In fact, Roman soldiers used spider silk as a wound dressing 2,000 years ago.”

Spider silk is produced using a renewable resource—the mulberry tree—and is biodegradable, “so it won’t sit in a landfill forever,” says Rice.

“But beyond that,” he adds, “it just has incredible performance properties. It goes far beyond a fancy dress or really great bulletproof jacket.”

Sidebar: Sustainable sourcing

Sustainable sourcing/tracing—including DNA testing, knowing the full background of where the product started—is an increasingly important issue for many companies in the textile industry, including DuPont Biomaterials.

Here’s an example of how it works at Dupont, according to Renee Henze, global marketing director for the company, which is based in Wilmington, Del.:

“The process begins with industrial dent corn, which is corn grown for animal feed and other industrial uses and not suitable for human consumption. Dupont’s Sorona® component is one of many co-products of this industrial corn. Glucose is extracted from the corn kernels and microorganisms are then added to begin a fermentation process. This creates a monomer, known as Bio-PDO™ (1,3-propanediol), which DuPont scientists spent decades researching.

“The fermentation replaces chemical synthesis to produce PDO in a natural, more environmentally-friendly way. The PDO is then added to a petroleum-based monomer to create long strands of the Sorona polymer, which are cut into pellets.

Yarn spinners use these pellets to create fibers. Then mills use those fibers to create fabrics. And then manufacturers and designers use that fabric to create the eco-conscious apparel that consumers purchase and wear every day.”

Jeff Moravec is a freelance writer from Minneapolis, Minn.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG