At age 19, Karl Deardorff bought a sewing machine from Leo Robbins, his first sailing instructor. “I wanted to be able to fix and alter my own sails,” he says. The machine went with Deardorff to California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, where he was also on the sailing team. Soon he was doing small piecework jobs for people in the sailing community and had landed a summer job with a sailmaker.

After graduating with a degree in industrial technology, Deardorff worked for a few years at a sail and boat cover manufacturer in Austin, Texas, before returning to San Luis Obispo in 2005 to reconnect with his former college roommates and start a business—SLO Sail and Canvas.

“We were all spread out across the country and said, ‘Let’s move back to SLO [San Luis Obispo] and keep having fun there,’ and within a few months, one of the guys had rented a house, and we all moved in,” Deardorff says. “SLO Sail and Canvas started in the garage of that house.”

Taking notes

Deardorff had always paid attention to the marketing and operations side at shops where he worked, knowing that he might want to go into business for himself someday. One valuable observation was the importance of offering different product lines to balance fluctuating demand.

“The first shop I worked for did sailmaking and repairs,” he says. “The second did boat covers, bimini tops and shade products in addition to making sails, so when I started SLO, right from the get-go, we were focused on those four areas.”

Early success came from targeting a handful of boat dealerships in San Luis Obispo. SLO was the only local custom cover manufacturer, and latent demand kept SLO busy for a few months. When those orders tapered off, Deardorff decided to try selling Laser sailboat covers for $99 on eBay—controlling postage costs by using USPS flat rate shipping boxes. Sales were healthy. Realizing the potential of online sales, Deardorff reached out to a programmer friend and expanded SLO’s website to include e-commerce.

“Within just a few months of doing that, things changed really fast, and that’s when the business started growing very quickly,” Deardorff says. Selling marine covers online was still a relatively new idea at the time, and it took a few years for SLO to work out the kinks—for example, transitioning from tightly fitted custom parts to those that were more fit tolerant.

Big, weird parts

As much as Deardorff took note of the product lines at his previous jobs, he perhaps more closely observed shop operations and setup—and thought a lot about how to organize a facility for maximum efficiency. When SLO outgrew the garage in 2007 (and his college buddy/partner fell in love and moved to Los Angeles), Deardorff brought his experiences and ideas together in the company’s first warehouse and workshop space, building it out according to his specifications. This included digging out the concrete floors so the sewing machines could be recessed and raised or lowered depending on the size of a project the company might be working on.

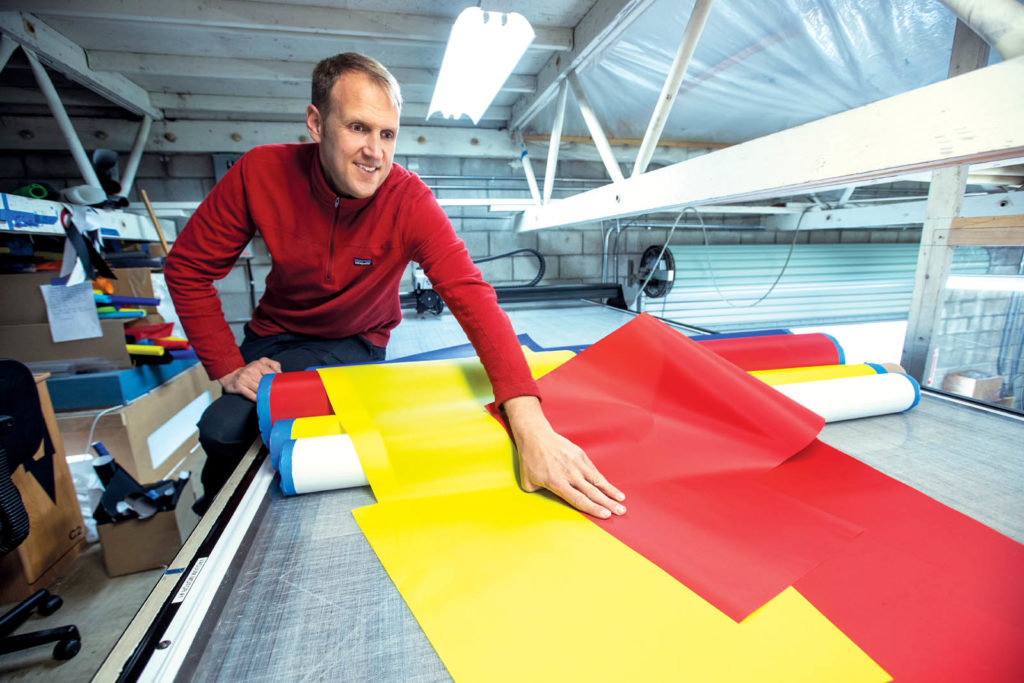

“We’re really good with big, weird parts,” he says, referencing one defense subcontract job that was 70 feet by 70 feet and weighed 250 pounds. Over the past 15 years, SLO has continued to refine its processes and equipment, and Deardorff cites a few purchases that have made a significant impact: sewing machines with needle positioning, a Carlson automated cutter that he found on eBay for $4,000, and the subsequent purchase of an Autometrix laser cutter. In addition, the company has grown physically, adding a second warehouse two years after the first and a third more recently.

From sea to space

Deardorff credits a summer employee for SLO’S entry into the aerospace market. “One of the guys who worked here in college became a fueling engineer at nearby Vandenberg Air Force Base and thought of us when they had draping projects,” he recalls. “And now we also do work for other aerospace companies who find us online.”

Early frustration translating designs from engineers accustomed to working with metal turned into an opportunity for SLO to educate those engineers on the different properties and applications of textiles. The partnership has resulted in better designs and more efficient and profitable projects for SLO, with aerospace now accounting for about 30 percent of the company’s business.

Over the years, SLO has hit a few bumps in the road, including a brief foray into shade sails. “That didn’t go well for us. My hat is off to those who have figured it out,” says Deardorff. “There were too many options and decisions to make, which wasn’t a good fit for our operation.”

Another challenge has been maintaining and updating the shopping cart software on the company’s website. SLO has been through three so far, and it’s an ongoing challenge to find the right solution. “I don’t know how to internet well,” Deardorff jokes. “I know how to sew.”

Controlling the process

“I was an IFAI [Industrial Fabrics Association International] freeloader for the first 10 years,” Deardorff confesses. He decided to officially join five years ago and said it was a smart move, giving him access to peers and vendors in addition to a sense of belonging. Deardorff also notes that going to IFAI Expos and connecting with other members has paid tremendous financial dividends. “Tens of thousands of dollars,” he says, citing one example—an automated webbing cutter the company wouldn’t have purchased without seeing it at an Expo and having the opportunity to talk to people who use it. “That saves us hundreds of hours. Cutting is so easy now we don’t even think about it.”

Like most small business owners, Deardorff spends his days talking to customers, fixing problems and managing his 12-person staff. During COVID-19, he also found himself doing more hands-on sailmaking, which he enjoys, and he thinks doing the work makes him a better manager. “The way to get control of the outcome is to get control of the process,” he says, “and the way to do that is to become an expert in that process, which in our business is sewing.”

Laurie F. Junker is a freelance writer based in Minneapolis, Minn.

Photography by Tom Meinhold Photography

SIDEBAR: Project Snapshot

Technical wonders

While a sail might seem like a straightforward piece of sewing, it’s actually more technical than people realize, according to Deardorff. “Sails are complex 3D shapes that can have corner loads measured in tons. They have to perform well from an aerodynamic, durability and aesthetic perspective, all while keeping price in mind.”

For a typical project, the design process involves basic rigging measurements, 3D shaping and computational fluid dynamics analysis (how water flows over a surface) to make sure the shaping is correct. For larger racing sails, SLO also uses software to perform an aeroelastic analysis to load the sail with wind and analyze the flying shape along with drive and drag curves and other parameters. SLO often tests three to five different designs before choosing the best option and cutting the sail.

Deardorff is quick to point out that as important as computers are to modern sailmaking, they haven’t replaced the human touch. “Some sails involve extensive handwork, creating a connection to ancient sailmakers that would have sewn their own sails thousands of years ago. The wind will continue to power us for thousands of years to come.”

SIDEBAR: Q&A

What is an interesting trend in the sailing market?

COVID-19 has gotten a lot more people into sailing. We saw a significant uptick in business in 2020. It’s cool seeing sailing become more popular. When soccer and other youth sports were put on hold, people spent that money on a sailboat—a hobby the whole family can enjoy. I think that’s pretty great.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG