or Beverly Hills abode of a movie star.

How about a new National Co-operative Advertising Campaign?

Early in IFAI’s history, the members realized that a prime goal of the organization should be to help all members expand revenues and profits through collaborative thinking and shared best practices. An article in September 1916, under the headline “Hot Days and The Awning Business,” made the analogy of the impact that national agricultural coalitions, through focused campaign promotions, were having on local grocers—suggesting that awnings could be promoted in a similar way. “The grocer receives a profit on handling oranges, but the fact remains that the California Fruit Growers Association … vastly multiplied the consumption of oranges by working upon the ultimate consumer. Then the Tent and Awning Manufacturers can greatly increase the use of awnings by publicity upon the tenants who will demand the building owners to equip their block with protecting awnings.”

By 1925, IFAI was developing a National Co-operative Advertising Campaign. The key word here is co-operative. Understanding that its impact could be multiplied by the force of numbers, the National Canvas Goods Manufacturers Association put money and effort behind a strategically focused campaign, developing a series of professionally designed ads that members could use as “drop-in” advertisements for placement in local papers and magazines, allowing space for the member firm to include its own name and contact information.

Cooperation was the theme that year, launched by the association’s first executive director (and editor) James E. McGregor’s own unique call to action: “During this year of 1925, let us forget our petty jealousies and prejudices, and remember only that we are brothers and neighbors, made alike in the image of God, going the same journey, sharing the same destiny. If we will do this we will soon rise into the power that comes from working together.” Letters to the membership encouraging each member to participate were sent out noting the increase in building “in every city of the United States” that occurred the year before—surely offering an increased opportunity to sell more awnings.

Advertisements for the most part were black and white with illustrations, but by mid-decade began to exhibit “spot” color (isolated color highlighting an illustration), and by the July 1928 issue the magazine featured its first full-color cover, a beautiful, lushly landscaped home with striped awnings captioned “The Broadmoor,” professionally illustrated, suggesting the Bel Air or Beverly Hills abode of a movie star.

Working with architects

By 1931, an increase in the amount and variety of display advertising within the magazine indicates that suppliers of hand-held electric cutting machines, sewing machines, waterproofing treatments and awning hardware must have felt confident that business was steady, despite the stock market crash of 1929. The cost of goods and labor, however, continued to underscore many aspects of the industry, and McGregor ran a series of columns for several years on costing and estimating.

A.J. Messells (listed simply as “cost manager”) wrote a column in the Feb. 1931 issue about the importance of reaching out to local architects entitled “The National Members Now Make Contact With the Architect.” He commented: “At the present date there has never been any attempt made nationally to educate the architect and contractor on how an awning should be constructed onto [sic] a building. The beauty and color of awnings have never been forcefully brought out by the manufacturer in his occasional relationship with the parties who plan and construct the building. Consequently there has been no growth in this market through these channels.” The author suggested meeting the architect halfway by urging awning manufacturers to use blueprint drawings to show how their products could be integrated with buildings, using a common “language” to communicate.

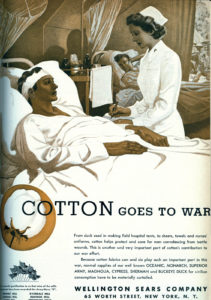

We don’t know how many members may have found success with this strategy, perhaps due to the gradual shift in focus in the late 1930s and early 1940s toward the ominous threat of another European war, and the national government’s growing grip on controlled material usage directly affecting local businesses (the editor noted “a deleterious effect on our economic structure” and “a hollowing out of small businesses”). Within the Review, especially by 1943, nearly every ad—from full-page down to quarter-page size—paints the products in a curious bi-furcated style that acknowledges the war efforts as well as attempts to promote products for use in regular commerce (“in peace time and in war time”), showing products in photos of military and in local commercial settings.

As might be expected, this style quickly changed after the war. For example, a Sept. 1946 issue advertisement reported that one member firm was recently venturing into canvas houses “to help relieve the housing shortage,” noting that they used specially coated (“Fire Chief Finished”) cotton duck canvas.

The new consumer

With the easing of material restrictions after the war, manufacturers were free to reinvest in R & D and the development of new markets for new products. Public relations for the new consumer society became a science as well as an art, most notably led by the automobile industry and the proliferation of a new medium: television. The Review recognized that members would need new tools for promotion and marketing if they were to hold onto the advances made before the war. A March 1957 issue started a series of columns on public relations for small businesses, written by public relations experts from outside the textile industry, offering insight and short courses in “marketing basics,” “modern marketing” and “new market opportunities.” The series ran through 1959.

By the 1960s the emphasis changed to promoting the benefits of fabric products to each market. For example, instead of selling awnings, the Review suggested (as it once did in the 1920s) “we’re in the business of selling shade.” Readers were encouraged to promote their expertise as professionals with high-level skills offering quality work, all the while paying close attention to the bottom line. This is a tactic that finally paid off in the 1970s and 1980s, when communities across the country started rediscovering their historic districts and tried to recapture the few buildings and settings of significance left after the modern rebuilding rush that began after WWII. Many fabricators found new markets in recreating the awnings of their grandparents’ era for the retrofitting and preservation of older structures.

Efficiency with convenience

New products from Europe begin appearing, such as motorized retractable canopies and awnings in compact, efficient units that could be easily adapted to clients’ needs, opening still more niche markets. The U.S. has always been behind Europe in the use of retractable awnings (many point to the use of air-conditioning as one big reason for the disparity), but with the advent of increased concern for energy efficiency and the new motorized controllers, their popularity has increased.

“The retractable screen and awning was a game changer,” says Bruce Dickinson, vice president of sales for Rainier Industries Ltd., Tukwila, Wash., “especially for energy savings and sun protection.” The concern for energy-efficient buildings and practices also impacted the industry as local governments and companies saw the demand for increasingly efficient operations and reduced environmental impacts, and how they could be enhanced with fabric shade elements.

By the 1990s and into the 21st century, new media began to change the way businesses marketed to clients, and any firm without a Web presence found it was being left behind on the competitive front. “This is a much faster paced business world than 20 years ago,” says Dickinson. “What someone can see in scrolling a website can impact immediate results.” The marketing game continues apace: today social media marketing—including Facebook, LinkedIn® and other platforms—directs new business planning and communication with customers, as each company learns which tools work best for which markets.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG