Fabric coatings and finishes have played a role in iconic pieces of America’s past and, with new technology, are poised to play a role in a more environmentally sustainable future.

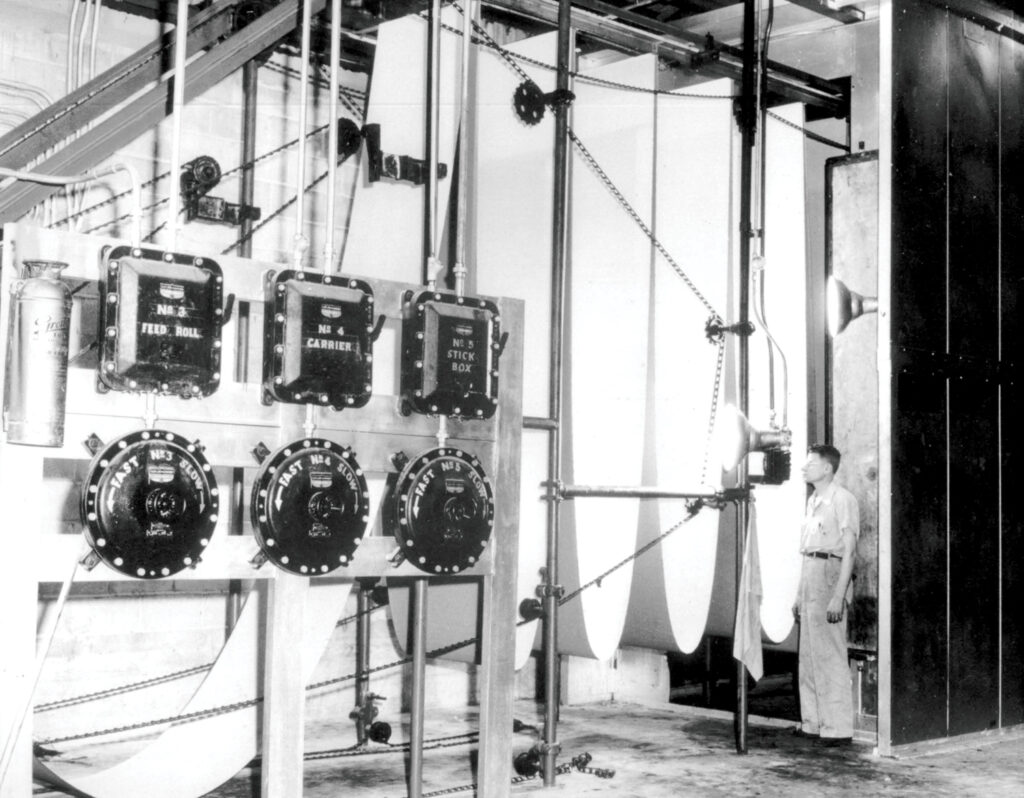

Graniteville Specialty Fabrics’ history dates to the 1845 founding of a textile mill in Graniteville, S.C. Today’s company is an offshoot, begun in 1947 after Graniteville Mill vice president Henry Woodhead invented a striping machine for the awnings of Woolworth’s five-and-dime stores. Previously, explains Graniteville Specialty Fabrics chief operating officer Doug Johnson, “If you wanted a design on your awning, you literally got a can of paint and painted the awning yourself.”

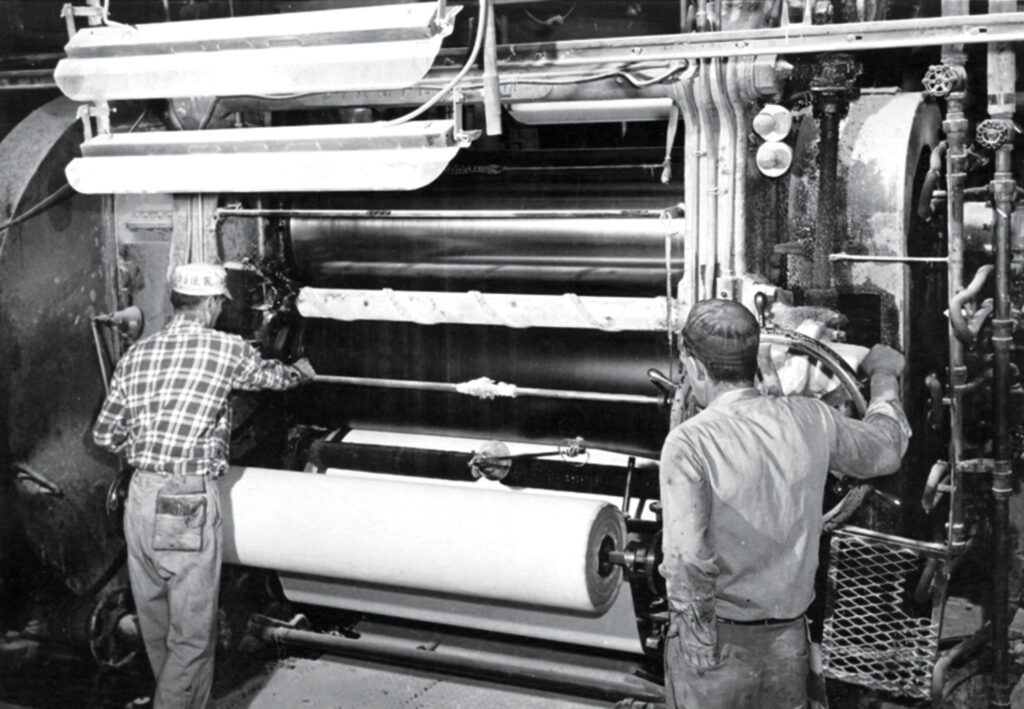

For The Haartz Corporation, located in Acton, Mass., with current ownership being the third generation of the same family since its founding in 1922, the historical tie-in comes via automobiles. Early products were coatings and fabrics for convertibles and soft-tops, dating to the earliest days of open-air driving. According to Samit Sadavarte, Haartz’s director of business development for new markets, “every now and then” the company gets a request to match a color or pattern for these vehicles. “Sometimes we have to go back in our old logs and try to see ‘How did we make that product?’”

By the mid-1990s, Haartz was expanding its products into automotive interiors, such as moldable trim products like door panels. At the time, Haartz was using extruded polyvinyl chloride (PVC) coating on those products. Now, Sadavarte says, more than 90% are thermoplastic polyolefin (TPOs).

Over the years, Sadavarte says, TPOs have evolved “so that now you can get superior touch-feel properties compared to PVC.” Additionally, PVC uses phthalate-based plasticizers, now restricted in several states, for softening properties. When exposed to high heat, the phthalates migrate to a product’s surface and escape, creating brittleness. “So applications like instrument panels, where it sees a lot of heat, the TPOs actually do much better” in terms of longevity, he says. TPOs, he notes, are 20%–30% lighter than PVC, with a corresponding smaller carbon footprint.

Shifts in products and processes

Another shift within the finishes industry is from solvent-based to water-based products. Both Haartz and Graniteville are moving in this direction. Graniteville also updated its coating range equipment to a system that can handle both water- and solvent-based products. “Even when we use solvents,” Johnson notes, “the way we use them is a little bit different. It’s still an environmentally friendly application.” When using the natural gas ovens for solvent-based coatings, “We actually use the [volatile organic compounds] VOCs coming off the coatings as fuel for that oven system,” Johnson says, reducing emissions and making the process more carbon-neutral.

Additional new equipment at Graniteville, says technical sales manager Sydney Price, includes a closed-loop system sprayer for applying water repellent. Rather than needing to squeeze out excess of a chemical application, “It just applies what you need to the face side rather than the whole substrate.” The closed system, she notes, also captures back the chemistry, and due to its more concentrated solution, reduces the amount of required water.

Haartz has worked closely with Green Theme Technologies Inc. to evaluate its patented EMPEL™ technology, a process in which a water-free chemistry is polymerized directly on the textile matrix under heat, pressure and inert conditions. EMPEL is also free of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

At first, says Sadavarte, Haartz is targeting applying EMPEL technology to applications that require a demanding durable water repellent finish, such as military protection and outdoor furniture. With traditionally applied finishes, whether or not they contain PFAS, you’re likely to see water passing through the fabric of an outdoor furniture cushion after it rains. “With EMPEL, we’ve seen extremely high water pass-through resistance,” he says.

Additional developments in polymers, says Price, include working in cooperation with chemical suppliers to redevelop those with traditional chemical formulations, such as ones that rely on petroleum. For example, Graniteville plans to launch a biologically based wax coating as an alternative to paraffin wax by the end of 2024. The product, says Johnson, uses some plants’ natural hydrophobicity and could be applied in the companies’ industrial and consumer markets, whether it’s for apparel or tent liners.

For several years, Graniteville has also used a polyvinyl butyral lacquer made from recycled windshield material of old cars as a polymer. “It’s an extremely good lacquer because it can form a web and has film integrity, which made it great for lawn furniture, for the outdoor cushions,” Johnson says. Today, the company uses the product as an economical polymer for ironing-board covers, many of which are used in the hospitality industry.

Additional recycling efforts at Graniteville include using scrap vinyl and acrylics to create new plastisol and polymers. Instead of offcuts going into the landfill, Johnson says, “We blend it, sometimes with virgin material, to get the use out of it again.” Such recycled polymers are used in awnings, boat covers, construction and automotive applications.

Both companies use recycled material in their products, whether that’s postconsumer recycled polyester or nylon or, in Haartz’s case, postindustrial recyclables. “A lot of the products that we make, our customer would use in the form of a convertible top or door panels. There are a lot of cutting materials that may go into landfill,” Sadavarte says. “We are developing products where we could take that industrial recycle from our product, regrind it, bring it back and use it.”

End-user influence in finishes

Although the companies partner with textile and chemical suppliers, the end user can have the most impact on what gets produced. Purchasing fabrics dyed with recycled textiles or food industry byproducts such as almond shells requires buy-in from a brand partner, Graniteville’s Price says. Although customers are aware of environmental regulations, she says, “We’re having

to change the expectation of what we can provide, specifically with the lack of oil repellency with the non-PFAS chemistry.”

Cost is also a factor for consumers. Since some bio-based or recycled polymers are not widely used, they’re more expensive than traditional options. “That’s really the biggest challenge: Even if you can find something that performs the same, how much more cost is it going to be and is the end user going to be willing to pay for that?” Price asks.

Haartz’s Sadavarte notes that original equipment manufacturers also are considering overall carbon footprint in purchase decisions. “So if we are making a synthetic leather that gets wrapped on an instrument panel, we have to do the entire calculation and say, ‘OK, this 1 square foot has 1 kilogram [2.2 pounds] of carbon dioxide impact.’ It’s not just ‘I’m going to use this bio-based chemical and now I have a sustainable product.’ We’re going to look at the entire picture.”

In that picture, he says, “You have to have that good balance between the environmental, the social and the economics. Sustainability comes at a cost.” Some bio-based products also may require more energy to process.

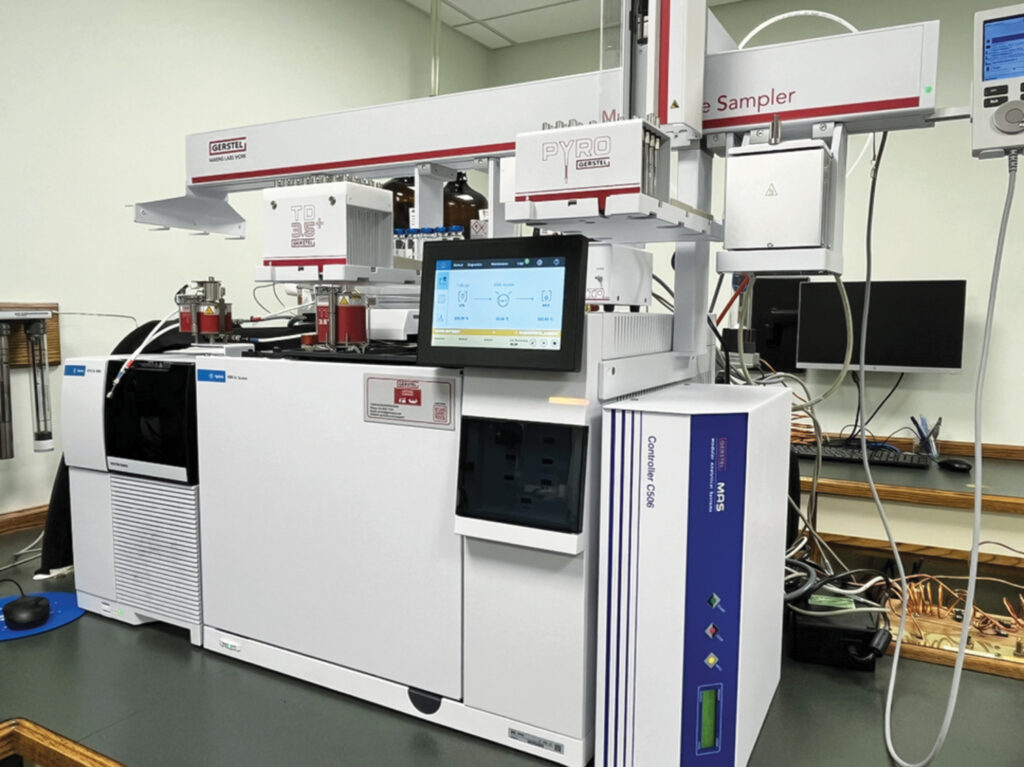

Such new products undergo testing at Haartz’s quality and performance lab to check for things such as heat and humidity exposure and flex, abrasion and wash durability. Both Haartz and Graniteville use xenon chambers to test for outdoor exposure. The Atlas Weather-Ometer®, says Price, puts kilojoules of exposure, correlating to sunlight, onto fabric. The tests, she says, are checking for “Does the fabric fade? Does it lose its strength? What happens to the coating after ‘X’ amount of exposure?”

Graniteville’s testing lab employs a subzero chamber to test if finishes crack or delaminate at temperatures reaching -40 F to -60 F. Plus, the company tests for flame resistance and for strength. “How much force does it require a fabric to break or tear or push water through it?” Price explains. Graniteville also has a development lab; about 30% of product development initiates with the company. The rest comes from customer requests, many of them custom. “We custom-formulate our coatings based on whatever needs our customer has, and we can custom pigment shade match,” Price says.

“About five years ago,” says Johnson, “we had a couple of our marine manufacturers come to us and say, ‘Can you make a black boat cover that doesn’t get hot?’” Additionally, the military wanted liners with temperature emissivity, “which is basically, if it’s hot outside, you try to keep the contents cool inside; if it’s cold outside, you try and keep them warm inside,” he explains. Using a blend of ceramics and metallics, Graniteville was able to respond to these requests and is now applying the technology to awnings and yurts.

“We’re just as much of a chemical company as we are a textile company,” Johnson says. “So the idea is to make some of these paints and plastics that we produce and not just apply them to fabrics but also to roofing materials and other items” that would benefit from the innovation.

At Haartz, where the traditional market is automotive applications, the company has already expanded into industrial, pipe rehabilitation, luggage, apparel, marine and defense areas. On the bucket list, says Sadvarte, are biocompatible surfaces for medical applications, smart surfaces and increasing performance, including higher durability and abrasion properties.

“These are all great challenges to have, and it’s certainly keeping us busy,” he says. “Overall, coatings has a great future.”

Joanna Werch Takes is a writer and editor based in Minnesota.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG