Finding, training and retaining skilled employees remains a vital issue.

Labor and workforce issues have always been an industry concern, and from the first issue to the current one, the Review has run frequent and regular articles about how readers can improve the bottom line by getting a better grip on finding and keeping valuable employees, skills training for employees and other related issues such as benefits and wages, all the way through succession issues, when business leaders step aside for the younger generation (family or otherwise). Major world events have also had a great impact in this area. World wars and military conscription, recessions and depressions and demographic changes have all affected labor trends in this country.

The Review has always sought to provide readers with useful and practical advice from experts inside and outside the industry. The Dec. 1925 issue featured an article by Mary Van Kleeck, director of the Department of Industrial Studies at the Russell Sage Foundation, entitled “Shared Management with the Workers,” based on research studies beginning in 1919.

The specialty fabrics industry has a good number of businesses that have been operating for a century or longer, but there isn’t always a family member who can or will take over the business.

The June 1930 issue labor column offered examples of internal training programs, and the Feb. 1931 and Nov. 1933 issues addressed the growing national concern of unemployment (at the peak of the Depression years.) President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Program of 1933 was enacted to regulate industry’s use of certain essential materials, and as a means to raise product prices and stimulate the economic recovery. Of particular concern to the industry was the growing use of “free” prison labor to produce canvas goods for national government use, a fact that prompted an impassioned editorial in the Nov. 1933 issue challenging the government’s unstinting application of the recovery program while undercutting member firms on price.

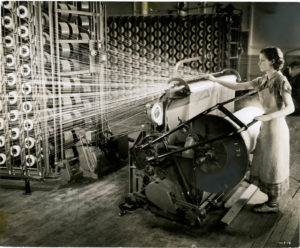

Continuing craftsmanship

With the onset of World War II, labor issues became more critical as more and more young men enlisted in the war effort and home front manufacturing was diverted to national use. Not to be outdone by the “heavy” industries of steel, automobile and truck (or tank) manufacturing or machinery and weapons manufacturing, the canvas products industries shifted production toward auxiliary goods such as truck covers, tents, decoy encampments or munitions plants (emulating Great Britain during the first world war, where camouflaged train yards, bomb manufacturing factories and other vulnerable locations were covered with fabric screens that, from the air, appeared to be forested groves). Although production easily shifted to making tents, covers and canopies for use in the war, labor (or more to the point, lack of labor) prompted an editorial in the May 1947 issue on how to keep those workers engaged and fully productive with challenging work. Parallel with those labor issues came concerns over taxes and modernization, when post-war rebuilding began and rapidly expanded.

By the 1950s, the proliferation and increasing strength of the labor movement prompted editor McGregor to comment, “I see no future for labor unions,” (Oct. 1957), and by the late 1960s, the Review shifted editorial focus to the need for craftsmanship and finding and training skilled employees, as well as a slowly dwindling market for traditional products (awnings, covers, marine fabrications) and the concomitant need for improved marketing and sales training. Mechanical air-conditioning units became more widespread during the 1960s; and despite the first Earth Day in 1970, energy consciousness didn’t really begin to build in the U.S. until after the OPEC oil embargo in 1973.

During the 1970s, business had sufficiently recovered that strategic performance reviews and ongoing internal improvement techniques began to populate regular columns in the magazine. Doing business had become complex enough—with growing international trade and competition—that issues including supply chain strategies and promoting and building stronger links between all sectors of the industry were coming to the fore. That lead again to more labor issues accompanying the need for new technical skills and automated manufacturing processes, sliding into the 1980s when coverage introduced issues such as a new United States service testing program (April 1981) and a concern for the need for more vertical integration of the overall industry. With new skills needed for employees, the Feb. 1984 issue of the Review suggested that awning shops should make a commitment to in-house “painting departments” and make substantial investments in new technology to incorporate commercial graphics, opening up the signage and graphics markets to awning and canopy manufacturers.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, prohibiting discrimination based on disability, affected employment and employee accommodations across the entire workforce and virtually every industry. Small businesses, like many specialty fabrics manufacturers, sometimes found it challenging to make all of the adaptations necessary to make their shops safe, efficient and up to date.

Gearing up

Heading into the new millennium, the Review refreshed itself with new graphics, a greater emphasis on photography and typography, and a renewed emphasis on workforce issues, as the dearth of skilled workers became a growing concern for many fabricators dependent primarily on sewn products. An aging population of longtime skilled workers (and management) has pushed this topic to the forefront again. “Finding staff is very difficult,” says Nora Norby, founder and president of Banner Creations Inc., Minneapolis, Minn. “It’s a huge issue primarily because it is hard to develop the skills needed for industry, especially the sewing portion of the workload. It really takes years of sewing practice. Many job applicants can have some skills with graphics, but rarely also have the sewing skills needed.”

Business succession is another problem facing many fabrication companies, which are often family-owned businesses. The specialty fabrics industry has a good number of businesses that have been operating for a century or longer (see “Members make the industry,” page 66), but there isn’t always a family member who can or will take over the business.

The issue of finding properly trained workers was so critical to a Chicago-based start-up business in 1992 that it prompted Pat Hayes, CEO and founder of Fabric Images Inc., to address the challenge head-on soon after opening his business. Hayes believed he had a new angle on the traditional exhibitry industry and knew that having the right staff would be key. “Labor is a blessing and a curse,” says Hayes. “How do you gear up for something that has never been done before? The workforce must be flexible and teamwork is essential in this situation. With the rapid growth and the industry changes going on in the 1990s, we could see that it required a whole different approach to the workforce.”

Hayes began working with ACT (the testing and profiling company most known for college aptitude testing) to develop job-specific relationship testing. These focused on “work-ready” core skills such as math, reading, locating information and comprehension. “As a nation,” says Hayes, “we are not efficient with our labor force. We don’t have the labor pool today that we had, even 20 years ago. Instead of putting someone on the job for 90 days and finding out they are not a good fit, a 15-minute work-ready skills test can match the applicant with the specific skills needed for a specific job. This way, we can measure the labor force by quality, quantity, growth potential (within the company) and ROI.”

What will the future bring? “I sense that people and clients will be asking for more tactile products,” says Norby. “Products with a ‘soft hand’ and pliable surfaces. People respond to the physical/tactile, and this is where fabric has an advantage over harder, rigid materials.” Norby agrees with Hayes that proper skills training and vetting will be essential to the future of the fabric products industry if it continues to grow as she envisions. IFAI has recently formed a co-operative agreement with the Makers Coalition to address many of these issues.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG