One of many crucial questions tent rental providers must help clients planning upscale outdoor events answer is whether they want a tension or frame-supported tent. Several factors influence the decision, from aesthetics to weather and space restraints to pricing. And while more clients are choosing the latter, tension tents are not without significant advantages.

Center pole appeal

“I love the aesthetics of tension tents,” says John Fuchs, general manager, special events, at Evansville, Ind.-based Anchor Industries Inc. “They have a very appealing and pleasing look you just can’t get in framed structures.”

“There’s so much you can do,” adds Darrell LeMond, owner of T.R.U. Event Rental Inc., also in Evansville. “The inside looks like you’re in a cloud. If installed properly, it’s the best-looking tent out there.”

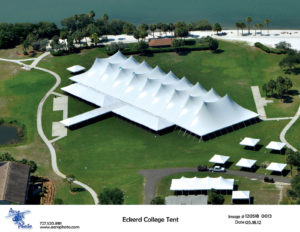

Most often used for weddings and large corporate or high-end events that conjure up classic images of high peaks, exuding elegance with their rolling curves, tension tents are supported by one or more center poles and secured to the ground with stakes. Cables or webbing—as opposed to just pulling tension on the fabric—run throughout to provide structure. Frame tents are instead supported by a steel frame, eliminating the need for center poles. They are easily anchored with weighted ballasts when stakes are not a viable option.

Christopher Starr, vice president of sales and business development at Starr Tent in Mount Vernon, N.Y., is partial to the twin pole tension tent. “It’s a beautiful looking tent that gives lighting companies and designers a spectacular palette to work off of,” he says.

Modular advantages

Tension tent measurements are driven by width, ranging from 40 to 120 feet, which makes them ideal for large events—while keeping length in check. “You want to avoid the bowling alley effect,” Fuchs says. “A rule of thumb is a 40-by-80 or 40-by-100 … a 60-by-120 or 60-by-150. You don’t want it to get so long that one end of the party doesn’t know what’s going on at the other end.”

Sizes are relatively standard across the industry. “Most of what we build are standardized modules,” says Alex Kouzmanoff, vice president of Torrance, Calif.-based Aztec Tents. “We’re not a job shop like an awning shop would be, but sometimes a customer will say, ‘You have a 40-foot-wide tent but I can’t fit that; I need a 39-foot-wide tent.’ For some tent designs, that’s fairly easy to achieve. For others, a lot more work goes into creating a new size.”

If a client wants customization, “without fail it’s going to be a frame tent,” agrees Bryan Bolt, sales manager of TopTec Event Tents, Moore, S.C., whose clients are increasingly requesting custom tents. Bolt’s company purchases both single- and twin-pole patterns from a tent designer or engineer. “We then have the sole right to build that tent in that style,” he notes.

Patterns are digitized on a computer before the material—typically vinyl—is rolled out, cut and then welded together via radio frequency. “Patterning is the biggest part of it,” Fuchs says about forming the tents’ illustrious peaks. “Each panel is unique; you can cut them in different shapes and tension them out into the shape you want,” he says, noting that the welding technique is not only a quick and easy way to seal the panels together, but also a way to avoid poking holes in the material, which helps with weather protection.

Weather resistance is also one of many reasons vinyl is the fabric of choice, as it’s waterproof and resistant to dirt and mildew. “It’s pretty much the king of what’s out there,” Fuchs says.

Bolt mostly uses 16- or 18-ounce laminated vinyl. “It’s durable; you can stretch it over and over and over,” he says. “Plus, it’s relatively inexpensive and easy to cut, seal and sew.”

Code constraints

Another key quality of vinyl is flame retardancy, which helps manufacturers meet fire codes. Complying with these, as well as building codes, is an ongoing challenge. “We work with engineers that tell us, basically, how to design the tent: what kind of bands, webbing and reinforcement, what the loads are,”

Fuchs says. “You build the tent in

order to meet the code.”

While the National Fire Protection Association(NFPA) is the primary governing authority for the fire code, every individual jurisdiction has the ability to modify what loosely exists as a national template for the building code, Kouzmanoff says.

“Codes are always changing. We spend a terrific amount of time helping our customers get the right certification so they can get the permit to get the tent set up,” Fuchs says. “It’s a moving target that’s very challenging to hit.” Independent certification firms can stamp off on certified tents, and Anchor has found success working with a St. Louis, Mo.-based company that is certified in all 50 states.

Safety first

Despite the hassle, code compliance is critical to the overall safety of the industry—but installation also plays a leading role, Fuchs cautions. “You can build the best engineered tent in the world, but it doesn’t matter if it’s not put up correctly.”

The majority of installation training happens on the job. “You can put the same size tent up 10 times and it’s a different situation every time,” LeMond says, adding that his team goes through safety training at least four to five times a year.

“We definitely do staff training, but there’s nothing better than on-site experience,” Starr agrees. In addition to basic safety and lifting procedures and warehouse and tent part training, Starr frequently has relatively easy set-up projects in the beginning of the year that are applicable for in-the-field training.

“I’ve learned a lot of what I know just by observing; it takes time to learn how to do this,” Bolt says. He serves as the lead instructor for TopTec’s Tent School, an installation and safety training program the company has hosted at its facility for more than 20 years. The company took the training “on the road” for the first time this year and held it at a customer’s location in Richmond, Va.; another session will be held in Memphis, Tenn., in December. Customers often send their sales staff as well as installers. “They have to put their hands on the product and do it; it’s the only way to learn” Bolt says, noting that the company also guarantees on-site installation training for new customers.

Staking vs. ballasting

When installing a tent, the holding capability is all about the ground, Starr says. “If you’re in a very manicured backyard with beautiful sod, the first 12 to 16 inches could be loamy topsoil that’s good for growing but not for staking.” This type of environment is more conducive to ballasted tents. However, tensile tents are tough to ballast, which is part of the reason demand for frame-supported tents is increasing.

“Stakes are better for their structure,” Fuchs explains. “Ballasting can be done, but the amount of weight that would be required to get the same tension loads makes it cost-prohibitive.”

Another challenge staking poses is the need for additional space around the tent. Starr explains: “An open, flat field is very conducive to a tension tent because if you have, for instance, a 60-foot-wide tent, you need an additional 16 feet around the tent—8 feet on all sides—to have room for the staking. So, if you’re trying to fit something into a small or restrictive space, sometimes you have to go with a clearspan just because the allowable space is pretty much the width of the tent.”

Market and demand

In his tri-state area, Starr has seen a major shift from tension tents to frame structures, specifically clearspans. “The tension tent has been the workhorse of the tent rental industry for the last 15 years, but the versatility and engineering of clearspans is more beneficial to the market we are in. Our area and other bigger cities around the country are more on the forefront of the trends of entertaining,” he says.

Fuchs and Bolt see more of a cyclical yet static demand, often depending on the economy. “It might go up two or three rentals every year, but it pretty much stays the same,” LeMond adds. Kouzmanoff sees a steady demand for the smaller sizes—the 40-by-60-foot range—but a decrease in the larger sizes—the 100-foot range—in favor of frame-supported structures. The cost advantage tensile tents offer, however, helps to preserve their prominence. “There’s not a lot of hardware to them, and there’s also the transportability; a 40-foot-wide pole can go in a small truck and three guys could install it,” Kouzmanoff says.

Starr echoes this opinion, recounting the recent set-up of a 50-by-70 tent: “It took two to three hours to unload and set the tent up from the time the truck got there. A clearspan of roughly the same size would take five to six hours and an eight- to 10-person crew, vs. a six- to eight-person crew.”

The cost of the actual acquisition of the assets—the tent itself—is more expensive for clearspan products per square foot than tension tents, Kouzmanoff notes. “You have to be aware of what your market is willing to pay, and that number changes greatly regionally. Listening to our customers is what helps us excel, because they drive our business. What always keeps us on our toes is our willingness to change and be flexible with what our customers’ needs are.”

Holly Eamon is an editor and writer based in Minneapolis, Minn.

From increased costs of labor to finding people willing and able to work, the lack of a skilled workforce is a big-picture issue many businesses are facing with the next generation of workers, says Alex Kouzmanoff, vice president of Aztec Tents.

“We talk about it all the time,” agrees John Fuchs, general manager, special events, at Anchor Industries Inc. “People just don’t want to work as hard. It’s a labor-intensive business, so how do we make it more labor-friendly?”

Through many years of training both new and experienced workers, Bryan Bolt, sales manager of TopTec Event Tents, has seen his share of first-timers not come back after a grueling day of installation. “It’s demanding work,” he says, “but when it’s all said and done, you have something to be proud of.”

Many tent rental companies adapt by keeping a small full-time, core crew and supplementing it with contract workers during the busy season, but for manufacturers “it’s hard to use temporary labor,” Fuchs notes. “We do use agencies, but we try to hire these people. Putting a tent together is really an art, from learning how the fabric reacts to making a smooth weld. Training is a huge expense for us, and once they gain some knowledge, we want to keep them.”

Making the workplace itself more appealing is one way Anchor tries to attract and maintain workers—a strategy that has also worked well for Kouzmanoff, who reports that Aztec has low turnover. “The key is creating a welcoming atmosphere and employee-focused culture within our organization,” he says, adding that “initiatives are focused on automation to increase the productivity and efficiency of our actual employees.”

Some rental companies are looking toward automation as well. “New technologies have helped reduce labor and increase productivity,” says Christopher Starr, vice president of sales and business development at Starr Tent. He mentions, specifically, the Tent OX™, describing it as a forklift with multiple attachments that can help drive and pull stakes, move material and put up center poles. “Companies that have this machine have said wonders about the reduction of the labor that you need to set up tension tents,” he says.

The automated route is not feasible for everyone, though. As the lead instructor for TopTec’s installation training program, Bolt offers manual installation methods that “take out a lot of the labor other people fight with,” he says—even solutions as simple as squaring the stake line a day ahead of time. But “people have to want to be trained,” he cautions. Whether those people are taking his training class or are potential employees eyeing the industry, this is the root of a problem that doesn’t seem to be going away anytime soon.

Tension tents are no small investment for a rental company, so inventory is meticulously cared for to get as many uses as possible out of each one. But any tent must be replaced at some point, Bryan Bolt, sales manager of TopTec Event Tents, affirms, which is when they’re often sold to smaller rental companies or donated for humanitarian causes, such as the aftermath of a natural disaster.

“We rarely throw anything out,” says Christopher Starr, vice president of sales and business development at Starr Tent, which employs several workers from Haiti and donated a large amount of supplies after the 2010 Haiti earthquake. “Our version of recycling is passing equipment to smaller, up-and-coming companies.”

Darrell LeMond, owner of T.R.U. Event Rental Inc., also breathes new life into old tents by providing leftover material to people who use it to cover firewood or to landscapers who need it for mulch. Alex Kouzmanoff, vice president of Aztec Tents, sees many tents that are past their prime become useful for construction projects or as shelter for storage.

Tent industry recycling is just in its infancy, says John Fuchs, general manager, special events, at Anchor Industries Inc. Bolt agrees, adding, “We try to minimize what scrap we have, but it’s still generated and we have not found a way to recycle that. Nobody has streamlined a good way to dissect that material because there’s scrim—a fabric that’s inside the layers of vinyl—and no one can pull that apart. It’s certainly an industry to be had that no one has really taken on yet.”

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG